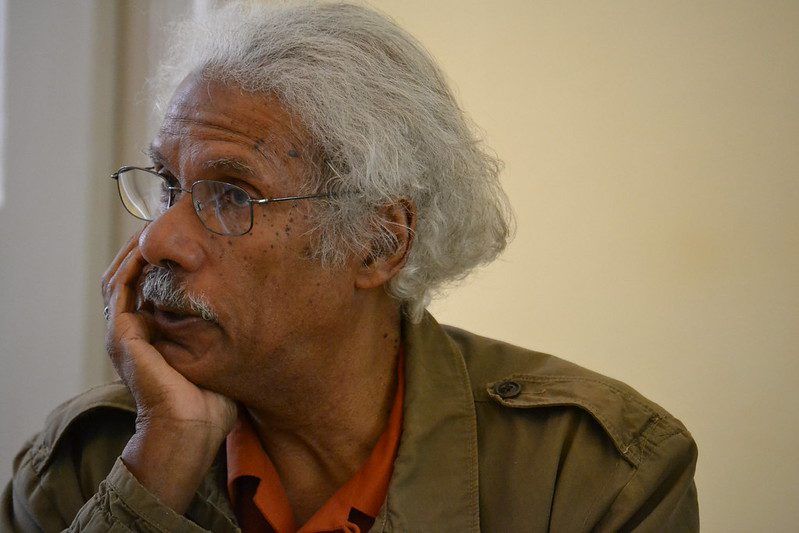

He would likely have declined the label highlighted here. But browsing the descriptions below I hope you will agree that Albert J. Raboteau (1943-2021) deserves that designation. In particular we do well to celebrate his legacy as a 21st century African American passion bearer.

In Eastern Christianity, a passionbearer (Russian: страстотéрпец, tr. strastoterpets, IPA: [strəstɐˈtʲɛrpʲɪts]) is one of the various customary titles for saints used in commemoration at divine services when honouring their feast on the Church Calendar; it is not generally used in the Latin [Roman Catholic] Church.[1]

The term can be defined as a person who faces his or her death in a Christ-like manner. Unlike martyrs, passion bearers are not explicitly killed for their faith, though they hold to that faith with piety and true love of God. Thus, although all martyrs are passion bearers, not all passion bearers are martyrs.

Passion bearer – Wikipedia

I first met Al Raboteau in the early 1980s while he was teaching at UC Berkeley; at the University of California there before he moved across the country to Princeton in New Jersey. I was a graduate student at the Graduate Theological Union nearby when he agreed to serve on my doctoral exam committees. He was a good mentor and confidant, meeting me in both office and home, and in later years even loaning me money as we became friends and colleagues. A great soul has passed on, generous and gentlemanly; an elder brother in faith and friendship.

In particular we shared a love for the Eastern Orthodox Church in its mystical traditions; admittedly an unlikely attraction for African Americans in these times. We met at conferences and workshops on connecting Eastern Orthodox traditions to Black religious experience, particularly in relation to his research in African religions and his standard in the field, “Slave Religion.” But he was capable of converting to Russian church orthodoxy at a level of transformation that I was not. Although I explored Eastern Orthodox ordination, and briefly considered even monastic orders, traversing such options required ‘a bridge too far’ for me.

Similarly but also differently from Thomas Merton, who incorporated Buddhism as a Catholic believer, Raboteau reached out to Eastern mystical Christianity as a Catholic who was also a black scholar. As an African American Christian with Eastern orthodox commitments he was also politically progressive. Consider for example his perspective on the climate emergency in this brief video.

Raboteau’s similarities with the mystical theologian Howard Thurman offer another comparison, as the two shared a passion for connecting mysticism to racial justice and the social gospel. But Raboteau was one of a kind: a unique combination of intelligence, service and passion for the life of the soul that the world will not see put together in that particular way again. A singular example of Raboteau’s Christ-like passion for souls is evident in the video below, where he describes meeting the son of the white supremacist who murdered his father. Here he strikes a balance between holding perpetrators accountable for their predations on the one hand, while holding open the option for reconciliation on the other.

Again, a great soul has passed on. Indeed our world is blessed to have hosted Albert J. Raboteau among us these 78 years. Now with this tribute I seek to honor you, good brother, while traces of your spirit still linger among us before you fully transition to your eternal home in the heavenlies.

Others tributes to Al Raboteau’s legacy follow below.

In Memoriam, Professor Albert J. Raboteau (1943-2021)

The Department of Religion mourns the death of Albert J. Raboteau, Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion Emeritus. Al’s research has left an extraordinary legacy in the field of African American religious history, African American Studies, and American religious history. His first book, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (1979), transformed our understanding of the religious experiences of the enslaved though his careful and empathetic attention to their voices and accounts of their spiritual lives, his presentation of complex theological grappling with suffering, and his recognition of the wisdom and joy of Black religious life in slavery amidst sorrow and violence. Many of his later writings, including the essays in A Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African American Religious History (1995) and A Sorrowful Joy (2002), are marked by incorporation of personal reflections about the stakes of the study of African American religious history as a Black man from Bay St. Louis, Mississippi whose father was murdered by a white man before he was born and as a Christian believer whose religious formation took place first in the Roman Catholic Church and in later years in Eastern Orthodoxy. Al’s scholarship also focused on understanding the relationship of religion to social protest, particularly in efforts for racial justice, and in his final book, American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals and Their Struggle for Social Justice (2016), he profiled a diverse group of figures whose spirituality and work had influenced, including Fannie Lou Hamer, Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Al joined the Princeton faculty in 1983, having taught previously at Xavier University in New Orleans, Yale University, and the University of California at Berkeley. He retired from the faculty in 2013, although he continued to teach occasional seminars in Religion and African American Studies over the next few years. He served as Chair of the Department of Religion from 1987 to 1992 and as Dean of the Graduate School in 1992-1993. He was active in the Afro-American Studies Program, contributing to its development over the years to the Center for African American Studies and now the Department of African American Studies. He was a founding member of the Center for the Study of American Religion that later became the Center for the Study of Religion and now the Center for Culture, Society, and Religion.

Al loved teaching and was a beloved teacher, advisor, and mentor to undergraduate and graduate students in the Department of Religion and many other departments and programs at Princeton, as well as other institutions where he served as visiting faculty. His courses at Princeton over the years demonstrated the breadth of his interests as well as the diverse sources and methods on which he drew to explore the role of religion in American society and culture. His courses included: “Religion and Nationalism in America,” “Afro-American Religious Movements,” “The Performed Word: Afro-American Religious Culture,” “African American Religious History,” “Catholicism in America,” “American Religious Radicals,” “Religion and Immigration in America,” “Holy Ordinary: Religious Dimensions in Contemporary Fiction,” “Re-Enchanting the World: Religion and the Literature of Fantasy,” and “Merton and King.”

Al received Princeton’s Martin Luther King Day Journey Award for Lifetime Service in 2006 in recognition of his work to advance King’s dream for America, and Princeton’s Howard T. Berhman Award for distinguished contributions to humanities in 1998, addition to numerous other awards and prizes for his research and contributions to the field. He delivered the Department of Religion’s 2018 Danforth Lecture in the Study of Religion on “Balm in Gilead: Memory, Mourning and Healing in Afro-American Autobiography.”

Judith Weisenfeld

Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion

Chair, Department of Religion

In Memory of Professor Raboteau

Dr. Albert J. Raboteau II died on September 18, 2021. He was the Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion Emeritus at Princeton University, where he made an institutional home from 1983–2013 and where I met him. His memorials and obituaries tell the story of his accomplished academic life, foregrounding his contributions to the field of African-American religion. His foundational books Slave Religion and Canaan Land were followed by others, some more personally inflected, including A Fire in the Bones, and what I might call his spiritual biography, A Sorrow Joyful. He discussed his last monograph American Prophets, published in 2016, in an interview for this blog. What I share comes from taking his course on African-American religion years ago, revisiting what was kindled in that classroom, and returning to his work over the years. They are heartfelt reflections and sparse memories, but cherished ones no less.

It was my junior spring, 1998, and I watched this renowned scholar enter our classroom in 1879 Hall on the first day of class. I was struck by his serenity and the way he lectured without raising his voice. His audibility relied on our silence and stillness and the universe of thought and experience he evoked in the room compelled it. For a semester, I sat in awe of the ways Professor Raboteau, as I remember him, narrated the devotional life that Black people in the US had crafted that could carry a state of captivity, foster a collective imagination, and cultivate the daily faith needed to sustain and nurture Black existence. The formation of a Black Christianity, the affective soundscape of gospel music, the Black church as a social, spiritual, and political home—these were the historical and social realms I felt welcomed into all the while being educated about the persons, including Raboteau himself, that made it possible for us students to sit in a classroom and learn about this history. Never before had I heard in an institution Black folks spoken of with such care and dignity. Never before had I encountered a professor who showed me that you could think and write knowledgeably and soulfully.

I remember my TA, who was one of Raboteau’s graduate students at the time, suggesting that I read the final essay in A Fire in the Bones. This kind TA (whose name I woefully no longer recall) related that this book was a treasure in Raboteau’s writing and one that might help my own. What stays with me is retrieving the book from the library, returning to my dorm room, and reading this short epilogue — an essay that weaves the story of Raboteau’s father’s murder by a white man into a meditation on the long history of Black collective loss and undeniable love that animate Black reverence. Alone in my room with tears in my eyes and emotion I could hardly untangle, I sat transformed by the knowing that scholarship could sound and feel so exquisite, and that the melancholy within me had ancestry and impetus. Raboteau called it “a sorrowful joy” a term he returned to frequently in his writing, to make palpable the emotional landscape that underpinned African-American spiritual life. He named a mood and offered a concept for tending to the interior lives of Black folks, that I have since explored.

“Life in a minor key” was more of the language Raboteau conjured to convey the fullness and mournfulness of Black life. His work illustrated the tireless holding of paradox: joy and sorrow, bondage and freedom, the flawed and the sublime. He also demonstrated how scholarship could serve personal, if not sacred projects. Reflecting on his research and memory work, he wrote, “I felt that in the recovery of this history lay the restoration of my past, myself, my people.” He showed me how to write Black life into a web of emotional and psychic complexity, neither tragedy nor exemplary, but profoundly human in its search for meaning and home.

Several weeks ago, a colleague invited me to discuss some of my writing for his undergraduate course on race and the environment. He unexpectedly asked if there was anything from my own undergraduate education that had shaped the direction of my work. Raboteau and his course came to mind. The connection is far from linear, but what arose, and what I share more clearly now, was how Raboteau’s philosophical and personal approach had bolstered my ability to wonder about Black understandings of the sacred and take seriously the forces of beauty, peacefulness, and stillness that seem to tether our material experience to something greater. In reading his rhythms and prose, I felt like I recovered a desire in my voice to write richly and intimately about Black people and to have the courage to contemplate the spiritual dimensions of ecological thought.

This past January, Raboteau’s daughter Emily tweeted that her father had entered hospice care. This was my first awareness that he was ill. In the months since, I have reflected and waited from afar, revisiting the class I took years ago. I’ve pondered his imprints on my intellectual life, and how he had provided a well-trodden path for embracing his eventual loss, and in general, the bittersweetness of life itself, felt so viscerally in these past years of global grief.

With him gone, and allowing the sadness to sink in, I feel his “sorrowful joy” and am more acquainted with what he tracked slowly as “sorrow merging into joy.” The loss I feel with his passing is consoled by the contentment and grace I experienced in the brief period in which I sat in his presence and teaching. The long history and tradition of Black spiritual life he conceptualized and archived will remain a touchstone and companion for my continued work on Black people. May others, especially those who did not have the pleasure of encountering him in the flesh, explore the breadth and depth of his written legacy. May he hear my memory and praise.